300 nanoseconds (1 of 2)

Educating people has always been a challenge for me. I tend to skip over things I wrongly consider obvious, or do large leaps in reasoning when explaining a solution to a problem. And so, when faced with an attempt to explain a complex topic, I tend to ramble on and on, hoping that the audience knows when to interrupt me if I go too fast. However, this doesn’t hold true for blog posts, such as the one I’m currently writing. This is why I have a request to you, the reader, please do let me know if I went too fast on this one - thanks!

So, why did I write this seemingly off-topic preamble? I’ve been trying to create a write up about performance in persistent memory programming and why it’s difficult. And my immediate thought was that it really is not and you should just follow the same old common sense rules you would for normal programs. It is just memory after all, but with higher access latency. But then, when I look back at the development history of libpmemobj, our memory allocator and transaction system, and the performance improvements we’ve made since the first version, I’m suddenly not so sure.

After all, if writing high-performance code for persistent memory were easy, we’d get it at least somewhat right the first time around. It’s either that or we were not as skilled as we thought we were back then. That’s certainly not beyond the realms of possibility for me, but the rest of my team? They are definitely quality folks. So… at an attempt to save face, we will operate on the assumption that my first instinct was wrong, and that crafting performant persistent memory code is hard after all.

What follows is my attempt at explaining why that is the case and how we’ve learned that the hard way during development of libpmemobj.

What is Persistent Memory?

But before we dive into the nitty-gritty details around performance, we first need to define what persistent memory is. I wish it were easy to do…

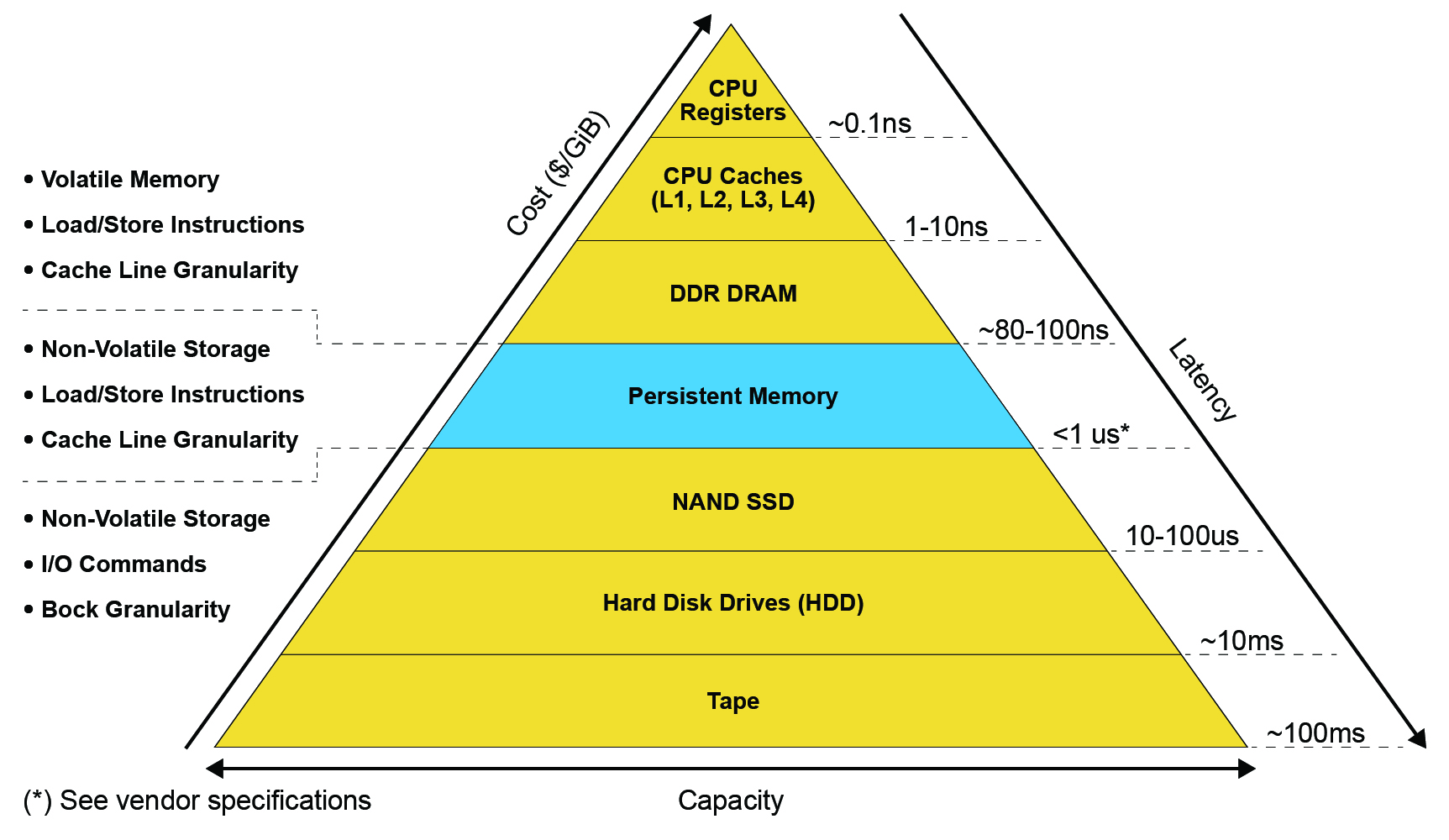

Depending on who you ask, you might get a different answer. The broadest definition that we commonly use is that it’s memory that is non-volatile and has access latency low enough that it is reasonable to stall the CPU while waiting for reads or writes to complete.

But that definition is so broad that, if we were to operate only within its constraints, it would make discussions around performance rather shallow and limited to the non-volatile aspect of persistent memory. In retrospect, this is one of the mistakes we’ve made when first designing the algorithms and data structures for PMDK. More on that later.

A more narrow answer is that persistent memory can be defined as a new class of memories, best characterized by a product X from company Y. For example, if you were to ask me, a paid Intel shill, what is this persistent memory thing, my answer would have to be: May I interest you in Intel®’s new revolutionary product, Intel® Optane™ DC Persistent Memory? I jest, of course, but it is my opinion that focusing on one category of products, as characterized by the most prominent example from such category, enables us to have a multidimensional discussion that captures more aspects of a given problem.

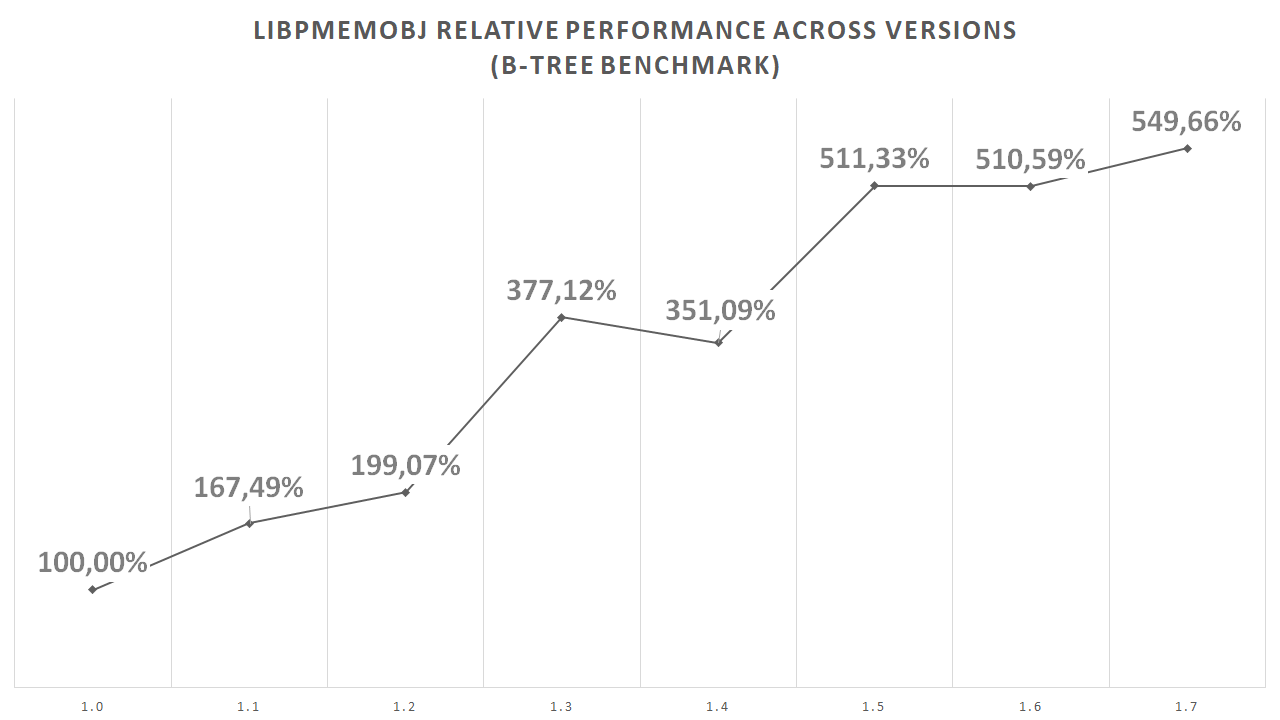

And this is how we finally get to the number in the title of this post. One of the more important characteristics of Intel’s new Persistent Memory devices is its average access latency. 300 nanoseconds.

Persistent Memory Programming Model

But that number alone doesn’t mean much until we put it in context.

So, is 300 nanoseconds latency fast? For storage it definitely is, literally orders of magnitude faster than any other technology. But for memory? Not really. It’s definitely fast enough to be considered memory, but it’s also not fast enough to be treated just like normal DRAM as far as data structure design is concerned. Especially when we consider the broader aspects of the Persistent Memory Programming Model.

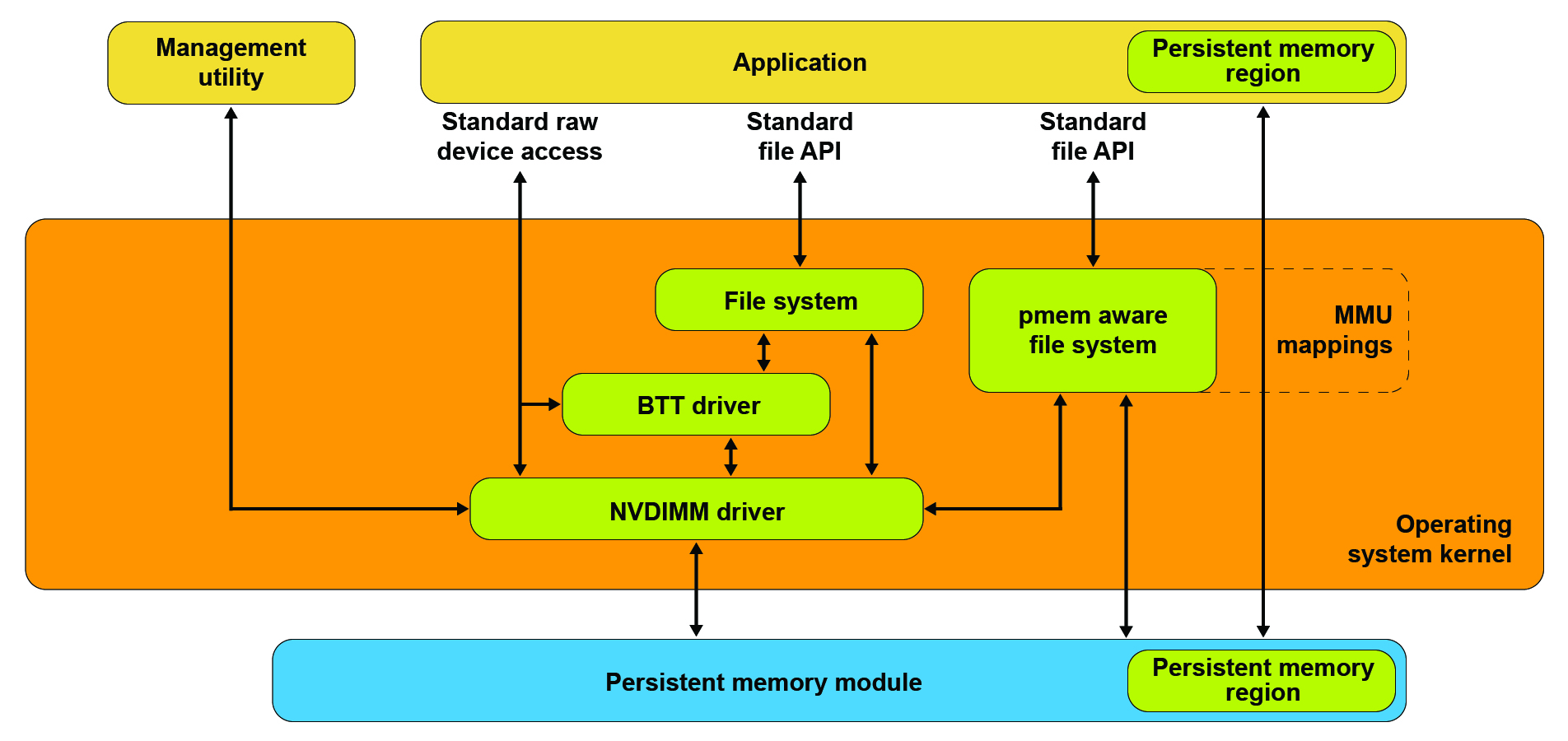

With persistent memory, just like with light, “we have two contradictory pictures of reality”. It cannot be simply described as memory or storage, because neither of those terms fully explains this new tier.

Just like with storage, it can be accessed through normal File I/O operations

such as read() or write(), and just like with memory, it can be accessed directly

at the byte level through Memory Mapped I/O, without an intervening page-cache layer.

And, just like with storage, the application needs to somehow synchronize

what it wrote to PMEM with the media, just like you’d issue fsync() or

msync() to make sure that your I/O made it all the way to storage device.

In fact, those two calls do exactly that also for persistent memory - but there’s

a better way.

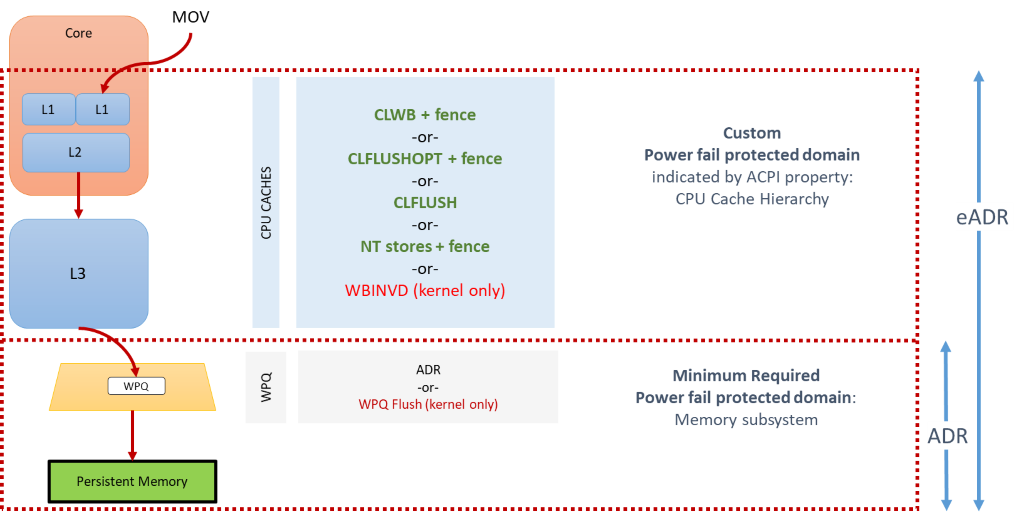

Let’s rewind a little first. I previously told you that persistent memory is non-volatile and you can write to it directly. So why exactly do we need to bother with synchronizing the I/O? Well, for the same reason we do it for regular storage devices. There are various caches and buffers along the way of a store from the application to the DIMM. Most importantly, there’s the CPU cache.

We consider a store to be persistent when it reaches the persistent domain of the platform. All stores that reside in the components that are within the persistent domain are ensured to reach the DIMM, even in case of failures, barring some catastrophic hardware problems.

To cut a long story short, in the common case this means that applications need to

push stores out of the CPU cache before it can be considered persistent.

You can do that with an msync() and the kernel will do the right thing,

but you also directly flush the CPU cache using user-space instructions, which

is beneficial for two reasons: a) there’s no expensive syscall, and b) data

can be flushed with cacheline granularity, not a page granularity.

Oh, and cachelines are 64 bytes on x86-64, meaning that stores smaller than that incur some write amplification when writing to the DIMM.

To sum up, persistent memory really is non-volatile, but stores need to be flushed out of the CPU cache, ideally using user-space instructions on individual cachelines.

But… (it seems like there’s always a but) cache flushing instructions evict the lines from the cache. Which means that reading something immediately after writing it causes a cache miss - requiring the CPU to fetch that data from the DIMM. And that’s not all. Even writing something again within the same cacheline after a flush will usually cause a cache miss, doubling the cost of a store.

Power-fail atomicity

All of that really doesn’t matter until you want to create some data structure that is actually persistent. And by persistent I mean a data structure whose lifetime is longer than that of the process which created it. However, that definition would also include data structures that are serialized when the process quits, a well-known approach which is out of scope of this post… because it’s boring. So, let’s narrow down our focus to data structures that outlive processes and are always consistent even in presence of failures. We usually say that such data structures are failure atomic.

That sounds eerily similar to concurrent (atomic) data structures, doesn’t it? Just replace “process” with “thread” and “failure” with “preemption”. This observation lies at the foundation of many ideas around persistent memory in academia and industry alike. To come up with efficient algorithms, we, the PMDK team, have been heavily taking advantage of the vast amount of work that’s been done for concurrent programming.

foo->bar = 10;

...

fetch_and_add(&foo->bar, 5);

/* visible = 15, persistent on DIMM = ? (10 or 15) */

persist(&foo->bar);

/* visible = 15, persistent on DIMM = 15 */

One problem with straight out using concurrent data structures for failure atomicity is the difference between visibility and persistence. Concurrent data structure have to guarantee that all threads of execution always see a consistent state. Persistent ones however also have to ensure that data is present in the persistent domain before other processes or threads are allowed to make any decisions based on the structure’s state. Doing this the right way is critical for performance.

A persistent doubly-linked list

To better understand what I mean, let’s look at an example.

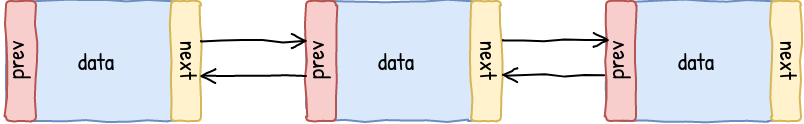

Each time an element is inserted into a linked list, there’s a need to:

- Allocate a new object.

- Fill it with data, including pointers to the next and previous entry.

- Update the

nextpointer of the left entry - Update the

previouspointer of the right entry.

To do this in a concurrent way we could simply surround these operations with some kind of a lock that would prevent other threads from accessing the list while there’s an ongoing insert. For the adventurous, writing a lock-free algorithm, that could maybe scale better, is also an option.

Easy-ish. (Yes, I know… just give me this one.)

Making it failure atomic however, requires us to answer a couple of fundamental questions. What does it even mean to allocate memory? The heap itself needs to be persistent. And we have to make sure that the allocated object isn’t leaked when something interrupts the program. The heap is persistent after all. Next, how will we make changes to multiple disjoint memory locations in a way that is fail-safe atomic? It’s not as simple as just preventing other processes from viewing our data structure while we modify it. The execution environment of our application can be brutally killed at any moment, forcing the next process that attaches to the same persistent memory region to somehow deal with the interrupted operation. And finally, we have to ask ourselves if this is really what we want to do? Is making a persistent doubly-linked list the goal? From my experience, creating a data structure or an algorithm is just a means to an end. Once we change our assumptions about memory a little bit, it might make more sense to reconsider our initial instinct of just using what we know.

With libpmemobj, in retrospect, we’ve incorrectly answered the first two of those questions, and failed to even ask the third.

And with this, I’ll leave you thinking until the holiday season is over :)

End of part 1 (of 2)

In this post, we’ve learned about what persistent memory is and how it can be used. We’ve also discussed what it means for a data structure to be persistent, and how that might affect performance.

In the next part, we are going to be diving deeper into my answers to the three questions I’ve posed, and how we’ve improved our libraries based on self reflections that we’ve had after we reconsidered our initial assumptions about persistent memory.

I wish you wonderful holidays and a happy New Year.