An introduction to pmemobj (part 2) - transactions

By now you should be fairly familiar with the basics persistent memory programming, but to make sure the application is always in a consistent state you had to rely on your own solutions and tricks - like the length of a buffer in the previous example. Now, we will learn a generic solution provided by pmemobj to this type of problems - transactions. For now we will focus on a single-threaded applications with no locking.

The lifecycle

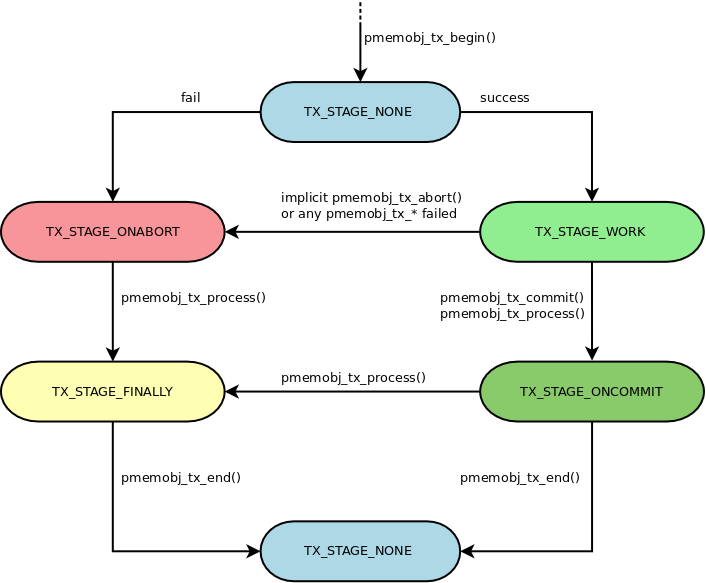

Transactions are managed by the usage of pmemobj_tx_* family of functions. A single transaction goes through a series of stages listed in enum pobj_tx_stage and illustrated by the following diagram:

You can see here how to use each of the stage-managing functions. The pmemobj_tx_process function can be used instead of others to move the transaction forward - you can call it if you don’t know in which stage you are currently in. All of this can get fairly complicated, for more information please check out the manpage. To avoid having to micro-manage this entire process the pmemobj library provides a set of macros that are built on top of these functions that greatly simplify using the transactions and this tutorial will exclusively use them.

So, this is how an entire transaction block looks like:

/* TX_STAGE_NONE */

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

/* TX_STAGE_WORK */

} TX_ONCOMMIT {

/* TX_STAGE_ONCOMMIT */

} TX_ONABORT {

/* TX_STAGE_ONABORT */

} TX_FINALLY {

/* TX_STAGE_FINALLY */

} TX_END

/* TX_STAGE_NONE */

As you can see this is very closely correlated with the lifecycle diagram, and pretty much self-explanatory. All of the code blocks apart from the TX_BEGIN and TX_END are optional. You can also nest transactions without any limits, and I guess recursive transactions are also technically OK. If a nested transaction aborts, the entire transaction aborts.

You might wonder why there’s the TX_FINALLY stage, why not just execute that code after the transaction block - well, due to the way our transactions work (setjmp at the begin and longjmp on all aborts), you are not guaranteed that the code that is directly after the TX_END in a nested transaction is going to execute at all. Consider the following code:

void do_work() {

struct my_task *task = malloc(sizeof *task);

if (task == NULL) return;

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

/* important work */

pmemobj_tx_abort(-1);

} TX_END

free(task);

}

...

TX_BEGIN(pop)

do_work();

TX_END

This snippet has a memory leak. The free will never be called, because the TX_END in do_work will eventually make a longjmp back to the outer transaction. The correct way of implementing the do_work is to use TX_FINALLY:

void do_work() {

volatile struct my_task *task = NULL;

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

task = malloc(sizeof *task);

if (task == NULL) pmemobj_tx_abort(ENOMEM);

/* important work */

pmemobj_tx_abort(-1);

} TX_FINALLY {

free(task);

} TX_END

}

This is OK because it’s guaranteed that the finally block will always be executed.

Please also note the usage of volatile-qualified variable in TX_FINALLY block.

This is because local non-volatile qualified objects have undefined values after

execution of longjmp if their value have changed after setjmp. So in the case

of libpmemobj transaction blocks every local variable modified in TX_STAGE_WORK and used in

TX_STAGE_ONABORT/TX_STAGE_FINALLY needs to be volatile-qualified - otherwise you might

encounter undefined behavior. Please see the CAVEATS section in libpmemobj

manpage for more information.

Transactional operations

Our library distinguishes 3 different transactional operations: allocation, free and set. Right now we will learn only about the last one, which - as the name suggests, is used to safely set a memory block to some value. This is realized by 2 API functions: pmemobj_tx_add_range and pmemobj_tx_add_range_direct. Quoting the documentation:

Takes a “snapshot” of the memory block … and saves it in the undo log. The application is then free to directly modify the object in that memory range. In case of failure or abort, all the changes within this range will be rolled-back automatically.

What this means is that when you call any of those two functions, a new object is allocated and the existing content of the memory range is copied into it. Unless the library needs that old memory in the transaction rollback, that object will be discarded.

Also, note that the library assumes that when you add the memory range you intend to write to it and the memory is automatically persisted when committing the transaction - so you don’t have to call pmemobj_persist yourself.

So how to use those functions? The pmemobj_tx_add_range takes a raw persistent memory pointer (PMEMoid), an offset from it and its size. So let’s set some values inside this structure:

struct vector {

int x;

int y;

int z;

}

PMEMoid root = pmemobj_root(pop, sizeof (struct vector));

The naive way of doing it might look like this:

struct vector *vectorp = pmemobj_direct(root);

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

pmemobj_tx_add_range(root, offsetof(struct vector, x), sizeof(int));

vectorp->x = 5;

pmemobj_tx_add_range(root, offsetof(struct vector, y), sizeof(int));

vectorp->y = 10;

pmemobj_tx_add_range(root, offsetof(struct vector, z), sizeof(int));

vectorp->z = 15;

} TX_END

But this isn’t very optimal - you are adding three objects to the undo log. I think it’s sufficient to say that a single undo log entry has size equal to, at minimum, 128 bytes. It is way better to just add the entire object at once:

struct vector *vectorp = pmemobj_direct(root);

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

pmemobj_tx_add_range(root, 0, sizeof (struct vector));

vectorp->x = 5;

vectorp->y = 10;

vectorp->z = 15;

} TX_END

This way you don’t waste unnecessary memory for metadata and the effect will be exactly the same. And it even looks better.

The pmemobj_tx_add_range_direct does the same thing, but in a more convenient way for some uses. It takes a direct reference to a field and its size, for example:

struct vector *vectorp = pmemobj_direct(root);

int *to_modify = &vectorp->x;

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

pmemobj_tx_add_range_direct(to_modify, sizeof (int));

*to_modify = 5;

} TX_END

This is useful when you don’t have an easy way of accessing the PMEMoid this memory block belongs to.

Conditional transaction blocks

It might seem that TX_ONCOMMIT and TX_ONABORT explanation isn’t really required, one is called when the transaction commits and the other one when it aborts - simple as that. As long as there are no inner transactions, that is true. But once we start nesting, things get a little bit more complicated. Consider the following example:

#define MAX_HASHMAP 1000

TOID(struct hash_entry) hashmap[MAX_HASHMAP]; /* volatile hashmap */

void hash_set(int key, int value) {

TOID(struct hash_entry) nentry;

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

nentry = TX_NEW(struct hash_entry);

D_RW(nentry)->key = key;

D_RW(nentry)->value = value;

} TX_ONCOMMIT {

size_t hash = hash_func(key);

if (TOID_IS_NULL(hashmap[hash]))

hashmap[hash] = nentry;

else

/* ... */

} TX_END

}

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

hash_set(5, 10);

pmemobj_tx_abort(-1);

} TX_END

So, a hashmap with entries in persistent memory but with a volatile table containing them. Is this code correct? Well, the hash_set on its own is perfectly OK - but not inside another transaction. When the pmemobj_tx_abort function is called everything in the TX_BEGIN block is reverted but the TX_ONCOMMIT of the nested transaction was already executed (and the TX_ONABORT won’t be called in that function), the end result is an invalid persistent pointer in the volatile table. This is generally difficult to solve and requires per-problem solution - I recommend designing your applications to actively avoid it. For this specific use case you can have an extra hash_revert_previous function that is called from the TX_ONABORT block of the outer-most transaction.

The intended use of the TX_ONCOMMIT and TX_ONABORT is to print log information and set return variable of the function with nested transaction, like so:

int do_work() {

int ret;

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

} TX_ONABORT {

LOG_ERR("work transaction failed");

ret = 1;

} TX_ONCOMMIT {

LOG("work transaction successful");

ret = 0;

} TX_END

return ret;

}

Example

We are going to modify the previous example to use a transaction instead of storing the length of a buffer. Open the writer.c and modify the lines after scanf to look like this:

TX_BEGIN(pop) {

pmemobj_tx_add_range(root, 0, sizeof (struct my_root));

memcpy(rootp->buf, buf, strlen(buf));

} TX_END

And that’s about it, looks simpler right? And more similar to how a volatile program might do this. The reader.c doesn’t change much, just remove the if statement that checks the buffer length and you are good to go. If you are having trouble correctly modifying the code, you can find the complete example here.

This can be further simplified by combining the two lines inside the transaction together - but that’s the topic for our next post.